Artworks and stories

by Julie Gough

© all rights reserved

The

whispering sands (Ebb Tide),1998 (Click

on the image or follow this link to see

another image from this series.)

The

whispering sands (Ebb Tide),1998 (Click

on the image or follow this link to see

another image from this series.)

This installation comprises sixteen lifesize portraits

pyrographically (hand-burnt) onto 5 mm plywood. These are British individuals

who historically and subsequently impacted on Tasmanian Aboriginal people.

These figures were placed in the tidal flats at Eaglehawk Neck, Southern Tasmania

during November 1998 in the 'Sculpture by the Sea' Exhibition.

These people were collectors; they accumulated material culture, stories,

human remains, anthropological/medical information and even Aboriginal children

in the names of science, education, history, anthropology and the increase

of their own personal status and power.

I decided (as an exercise and partially an exorcism) to collect these people

themselves (as images) and reduce them to a nameless conglomerate mass just

as they had enacted on Aboriginal Tasmanians last century.

Placed in the tidal flats for two weeks late in 1998, these figures submerged

and re-emerged with the action of the tides, the tide enacting the position

of memory. Placed as though they were wading into shore, they operated as

a form of mnemonic trigger. Their emergence from the water suggested that

their presence and deeds rests still within our own memories.

This work was a response to awakening ideas about our co-residency with the past, and to questions arising about our avoidance and consignment of the past to a peripheral dimension called 'history'.

Driving

Black Home, 2000 (Click on images below

or follow this link to see enlargements

of these works.)

Driving

Black Home, 2000 (Click on images below

or follow this link to see enlargements

of these works.)

15 postcards, Mantelpiece. Variable dimensions

Driving Black Home is an ongoing

series of photographic works I am compiling as I make my way around this island.

This takes time!

There are fifty-six places names after Black people in Tasmania, they include

:

Black Mary's Hill, Black George's Marsh, Blackmans Lookout, Black Tommy's

Hill, Blackfellows Crossing, Black Phils Point….

There are seventy nine "Black" places in Tasmania, they include:

Black Beach, Black Creek, Black Gully, Black Marsh, Black Pinnacle, Black

Reef, Black Sugarloaf, Black Swamp….

There is one Abo Creek in Tasmania….

There are three places named 'Nigger' in Tasmania: Nigger Head, Niggerhead

Rock and Niggers Flat….

There are sixteen places named for "Natives" in Tasmania, they include

:

Native Hut Creek, Native Lass Lagoon, Native Track Tier, Native Plains….

These are one hundred and fifty four places. But really they become one big

place, the entire island, Tasmania. This is a journey of mapping and jotting

the intersections which make up this place's story and history.

I see this big ongoing journey as an act of remembering . It is also

my way of considering and disclosing the irony that although our original

Indigenous place names were all but erased from their original sites; Europeans

then consistently went about reinscribing our ancestors' presence on

the land. I propose that these 'settlers' recognised the rights of occupancy

of Aboriginal Tasmanians' - evidenced by their renaming of 'natural' features

across the entire island in the image of Black, Native, Nigger and Abo….

HOME

sweet HOME (Click on images below or follow

this link to see enlargements.)

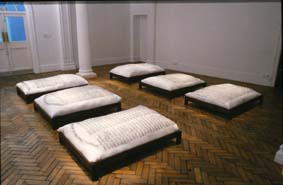

Gough,

Julie, HOME sweet HOME, 1999. Cotton, pins, timber, soap, installation.

Dimensions 6 x 6 m.

Gough,

Julie, HOME sweet HOME, 1999. Cotton, pins, timber, soap, installation.

Dimensions 6 x 6 m.

HOME sweet HOME eventuated as

a response to my visit to Liverpool in May 1999.1

When the former Bluecoat Hospital was suggested as a site for a work I began

walking around Liverpool noticing references to the great wealth upon which

the city was founded; the movement of people and materials – slavery,

migration and trade.

Initially I became engrossed in researching the transportation of people to

Australia – convicts, and the forced migration of children. However,

I found myself drawn, somewhat unexpectedly, to the children in the Bluecoat

Hospital (orphanage) who stayed behind.

The Liverpool Archives holds diverse references to the Bluecoat Hospital,

and also to the Ragged Schools and the Kirkdale House of Correction that existed

in this city; brief tantalising glimpses into a short life of hard work.

Children in the Ragged School in Soho Street, Liverpool 'sorted senna and

pig bristles' whilst children in the Bluecoat late in the nineteenth century

'made pins'.

The orphan boys in the Bluecoat Hospital were expected to set sail on the

Slave ships and Traders which were run by several of the Bluecoat Board and

Benefactors early in the nineteenth century. Girls were trained to be domestic

servants; if they defied this expectation they were not provided street clothes

to leave the premises.

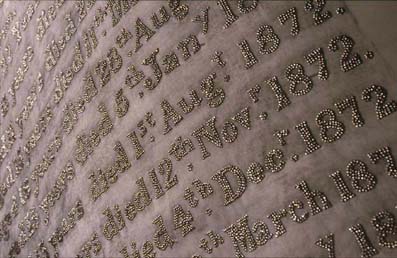

In wandering the city, I stood searching the cityscape from the top of the

Liverpool Anglican Cathedral and saw the cemetery below. I walked down through

the stone-tunnelled entrance into the underworld-like quarry burial-ground

of selected inhabitants of the city. Stone after stone inscribed with the

names of ship captain's and their ships, of dearly beloved and departed young

children eulogised in terms of permanent angelic sleep. In the midst of repetitive

notions of love and family I was stopped hard in my tracks by the sight

of six stones in a row. Damp and nettle fringed they unemotionally named-as-lists

one hundred and twenty-two dead children from four Liverpool Orphanages: The

Bluecoat Hospital, The Liverpool Infant Orphan Asylum, The Liverpool Female

Orphan Asylum, The Liverpool Boys' Orphan Asylum.2

I felt that these stones were

the answer, the reason for my extended walks in and around the city.

I imagined them immediately as soft pillows, as mattresses, as a comfort that

these children never had in reality. I returned to the headstones shortly

after with a huge bundle of cotton fabric and a large graphite rock from the

Liverpool Museum to rub and transfer the Bluecoat children to their former

site, and the other children to a similar Orphanage site to that which they

had experienced.

This activity occurred over six wet and windy days – with accompanying

unexpected vital meetings with cemetery locals and visitors.

I

then decided that soap should also be an element within the work. I

had been to Port Sunlight3 and seen the

influence of the Lever Company on the region. The unacknowledgment of palm

oil as a major item within the cargo of Slave ships – a direct connection

with Bluecoat (yet again), and this product's transformation into household

cleaning goods was a strangely repulsive and compulsive piece of information.

I

then decided that soap should also be an element within the work. I

had been to Port Sunlight3 and seen the

influence of the Lever Company on the region. The unacknowledgment of palm

oil as a major item within the cargo of Slave ships – a direct connection

with Bluecoat (yet again), and this product's transformation into household

cleaning goods was a strangely repulsive and compulsive piece of information.

Lavender scented soap mix utilising Lever LUX and lavender oil was applied

to the base of a plaster pillar in the installation. This represents both

the lack of mother and home comforts in these children's lives, and

visually expresses the metaphorical bar of soap upon which this building's

foundation and framework was based.

Upon my return to Hobart in late May 1999, I constructed small 'beds' for

these pillow/mattresses the size of the actual tombstones. I believed that

these names must be filled-in with pins. They became pin cushions with only

the pin-heads visible as an act of recognition and remembrance of the short

lives of these children. The dots were a form of punctuation - full-stops.

My mother, myself and three obsessively compulsive women worked continuously

over two months to complete the intensive pin-work required.

Making this work seemed to be an appropriately similar activity to the endlessly

repetitive work which the children's tiny hands endured as pin-makers, and

as such perhaps a fitting acknowledgment.

Seventy kilograms of pins later, and with enough stuffing for ninety regular

pillows – the children were brought back in from the cold to the Home

that wasn't so sweet for them.

Visitors to the room began speaking the names of the children aloud as they

read the pillows, invoking their presence and return to the very site where

they had dwelt over 100 years ago. They filled the gap of time with voice.

This aspect of sound, of naming, amongst the former silencing of cold headstones

was a most unsettling and generous act, beyond my intent, which unexpectedly

occurred.

Brown Sugar

Gough,

Julie, Brown Sugar, 1995/6. Acrylic paint on

ply, mixed-media. 1800 x 3000 x 120 mm. (Click

on the image or follow this link to see

an enlargement.)

Gough,

Julie, Brown Sugar, 1995/6. Acrylic paint on

ply, mixed-media. 1800 x 3000 x 120 mm. (Click

on the image or follow this link to see

an enlargement.)

This is a work based on the two-year journey of my ancestor,

Woretemoeteyerner, who travelled from Bass Strait to mainland Australia and

across to Rodriguez and Mauritius from 1825 - 1827.

The elements of chance and fragmentation are integral to the work due to the

information about the journey accidentally surviving within the vague diary

musings of Quaker Missionaries, Backhouse and Walker who, in 1831, recorded

that 'She spoke a little French.… Having been to the Isle of France'.

Further archival research revealed a little more; including that Mauritius

provides Australia with sugar to this day: once all types - today only demerara.

'Brown Sugar' has been utilised as a descriptive term for Black women throughout

White history. [For more text

relating to this work, follow

this link.]

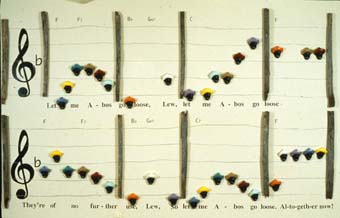

The Trouble

With Rolf

Gough, Julie, The Trouble With Rolf, 1996.Plaster heads,

Huon pine fence posts, fencing wire, text. Variable dimensions.

(Click on the image or follow

this link to see an enlargement.)

This work developed from the fourth verse of Tie me kangaroo

down, sport by Rolf Harris (1966).

The 4th verse apparently refers to a dying (white) pastoralist's last words;

his will and testament whereby he is giving away his 'property'. He mutters: 'Let

me Abo's go loose, Lew, let me Abo's go loose....They're of no further use,

Lew, so let me Abo's go loose, Altogether now...'

will and testament whereby he is giving away his 'property'. He mutters: 'Let

me Abo's go loose, Lew, let me Abo's go loose....They're of no further use,

Lew, so let me Abo's go loose, Altogether now...'

I represented one meaning behind the words by introducing plaster cast Aboriginal

stockmen heads, in a musical notation formation spelling-out the fencing-in

or out that has been enforced onto many outback Aboriginal people.

Rolf is probably also referring to the 'freeing' of Aboriginal stockmen/musterers

during the mid 1960's when the Equal Wages Bill was passed in Australia. Previously,

Aboriginal workers were paid a pittance, or with food/tobacco rations.

Paradoxically, the legislation resulted in thousands of rural Aboriginal people

facing unemployment and being forced off their traditional lands (where they

had often managed to continue living due to white 'landowners' allowing

them to work on these properties). It led to large numbers of Aboriginal people

living as displaced persons on the outskirts of townships, many up to the

present-day.

The song Tie me Kangaroo Down, Sport is a troublesome lyrical arrangement

because each verse except for the Fourth has Australian Fauna as its focus

- Kangaroos, koalas, platypus, etc. The fourth verse includes Aborigines as

part of the 'wildlife' of the Australian landscape, and then even goes so

far as to suggest that they can be 'let loose' - released at the whim of a

stockman/bushman - inferring that Aboriginal people were under the control

of others.

Yet this song is of it's own time, as was Rolf in the mid 1960's - can Rolf

be entirely castigated for proposing a pseudo freedom for the 'captives' ?

My aim in utilising the song and 'found' Aboriginalia (kitsch plaster wall

ornament of an Aboriginal stockman) which I then reproduced in multiple, is

to reclaim representations of Aboriginal people for ourselves. I believe that

the only way to work with imagery, text, inferences that are 'out there' already

performing their intended roles in society, is to claim these representations,

and reuse them subversively outside their original context.

The redirection into new performative roles of their power to damage and undermine

can question and redefine our understanding of that past in our country's

present and future.4

Julie Gough, © all rights reserved

Notes

1 I was invited to participate in 'TRACE' The Liverpool Biennial (Various venues across Liverpool) UK, 23rd September – 7th November, 1999 by guest curator Tony Bond (Curator from the Art Gallery of New South Wales). The resulting work, HOME sweet HOME has remained in Liverpool, but because this installation is an integral component of my PhD submission I discuss the work with accompanying illustrations here.

2 The deaths of these children occurred at various times and the headstones indicate their ages and these dates.

3 A soap making village adjacent to Liverpool which was established by Lever.

4

Interestingly,

Rolf has changed this fourth verse in recent sheet-music reprints of this

song, and he no longer sings the fourth verse as he originally intended either.

The trouble is, that like Eeny meeny miny

mo…music and verse are one of the most pervasive ways to enter into

the popular unconscious, and it will be some time before those familiar with

the song can replace the original version with the new. I think Rolf was reflecting

his times, and the mind-frame of most non-Aboriginal Australian's in the mid-sixties

– where I think he is still ensconced today. I believe that it is crucial

that this history hidden amidst the popular is not forgotten.